I had the unfortunate occasion to be present for many family recitations of the mourner’s Kaddish when I was a child. After my grandparents died, my mom and dad always went to shul for their yahrzeits. When my mother’s father passed away, I attended synagogue with her for a full year. When Kaddish time came, I remained seated when the name of my loved one was called, and it wasn’t only because I wasn’t of age. I can feel mother’s hand on my shoulder, making sure that I was staying seated. She explained to me that we sit as long as our own parents are living. I was glad to be sitting, and hoped to remain so forever!

As I grew up, the customs began to change. People stood “in solidarity with the mourners in our community” or “in memory of all those who have no one to remember them,” or “for the six million who perished in the holocaust.” How could I not stand for those? Yet, it felt wrong. A whole room full of people standing for every Kaddish meant that we are a community perpetually in mourning. And perhaps we are. But doesn’t it still take away from the person for whom mourning is a fresh and very raw experience. Should not their moment of Kaddish stand alone? Shouldn’t it be different than how they stood in all those previous weeks?

Some people tell me that they do not want to stand alone. There are solutions to this problem. Some communities have the mourners rise first when the name is read. Afterwards, the whole community stand alongside them. The mourners then recite the words of Kaddish surrounded by their community.

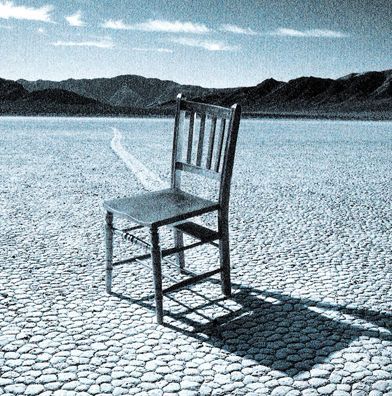

I am attending the annual conference of my professional organization, the American Conference of Cantors (www.accantors.org). I take this opportunity, when I am not standing at a pulpit, to remain seated during the Mourner’s Kaddish. As I sit in a room full of people standing, i feel so grateful. I am not ready to stand for the Kaddish. I will NEVER be ready. I sit alone and thank G-d for it!

I agree completely. I too have struggled with this issue. I grew up with the same custom, that only the mourners rise for kaddish. What I miss the most when the entire congregation rises is the opportunity to hear the voices of the mourners, to take note of their sorrow so that they can be approached with words of comfort. To hear the voices of those not in mourning, drowning out the voice of the mourner, creates another loss …taking away the mourners’ sacred moment.

An interesting issue; as with many it lies in one’s personal history and perspective. When I stand alone, I feel isolated. When others stand with me, I feel enveloped in the warmth of a caring community, from which I derive strength.

On Yom Kippur I always take a break from services during Yizkor. Though I have lost many who were dear to me, I have, remarkably, it seems to me, reached the age of fifty-five without having to say an obligatory Kaddish. On Yom Kippur I make a point of gratefully accepting this blessing by stepping out for a bit of sun, fresh air and conversation. I know it can’t last forever.

Thank God you don’t have to – sit as long as you can. You will never be ready for it, no matter when it comes. Just know that it will be a comfort to stand when it’s time.

My cousin recommended this blog and she was totally right keep up the fantastic work!

I never understood it until I had to actually be the one standing. I didn’t really get it, not fully, not in my heart. After my mom passed and I had to stand for the first time, not directly after her death (I was still in ‘shock’ then), but at her first Yahrtziet, it was when I really understood what it meant to stand in memory of someone you lost. I think I didn’t mind standing alone for the few minutes it took to read off all the names, but I was really very glad when everyone else stood up and I didn’t feel so alone anymore. But the nicest part was when a few people came up to me during the oneg and acknowledged my loss. That is what standing up alone (for at least the first few moments) does. It allows the rest of te congregation to see you and be able to know who you are so they can acknowledge you. It’s now many years later and I don’t really need comfort in the same way, but that doesn’t mean I don’t need / want to talk about my mom to someone who may want to listen for a moment or two. Standing up during Kadish allows that to happen.

It has long been my feeling that introducing the custom of having everyone stand for the Mourner’s Kaddish was one of the Reform movement’s big mistakes. Coming to shul for yahrtzeit was felt as an important obligation by many Jews who observed almost nothing else, and it kept them tied to the synagogue. If I’m asked to stand for Kaddish every Shabbos, then my yahrtzeit no longer stands out in the rhythm of my year, and my sense of obligation to observe it recedes.

I am totally unmoved by the argument of standing in solidarity, or of standing for the victims of the Holocaust who have no one to stand for them. (We observe their collective yahrtzeit on Yom Hashoah.)

I believe this practice came about in response to the Reform movement’s commitment to the halacha as written by Emily Post, and the teaching that we shouldn’t call attention to ourselves. Fortunately, at least for this matter, we are now in a period of narcissism, which is why congregations are moving towards the old way — as when the mourners are asked to rise first. And, although the minhag in my congregation is for everyone to stand, and although I usually believe in following minhag hamakom, I’m considering taking a stand on this issue, by sitting.