A Torah scroll is written by a Sofer, or scribe. The scribe must follow a lot of rules that govern how a Torah is written, on what, with which ink, and with which tools. Torah scrolls must be meticulously copied and not written by memory to ensure that each is exactly the same. As a result, scribal traditions have been passed through the generations and there are many places where smaller or larger letters appear. Since nothing is by accident, these become wonderful fodder for the rabbinic imagination.

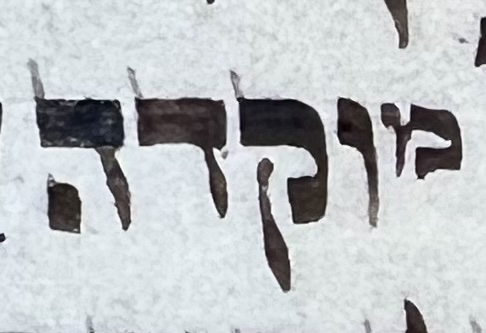

One such differently sized letter appears at the beginning of this week’s parshah, Parshat Tzav. In Leviticus 6:2, we read, “Command Aaron and his sons thus: This is the ritual of the burnt offering: The burnt offering itself shall remain where it is burned upon the altar all night until morning, while the fire on the altar is kept going on it.” The “mem” in the word “mok’dah” is smaller than all of the other letters. The Mok’dah was the hearth – the top of the altar on which the burnt offering was consumed by fire. So, why would this word begin with a small mem?

The altar symbolizes humanity’s service to G-d. The essence of prayer is humility. According to the Kotzker Rebbe, when we understand how small we are, and worship from that place of humility, we have a chance of connecting to how great G-d is. It is like how we feel suddenly very small, yet connected to the expansiveness of creation when we stand in an empty field and look at the star-speckled night.

We are tiny beings on an earth altar in the midst of an unmeasurable universe, yet like the trillions of cells that make our bodies function, we are an integral part of that expanse. It was said of Reb Simcha Bunem, a 18th century Hasidic rebbe, that he carried two slips of paper, one in each pocket. One was inscribed with the saying from the Talmud: Bishvili nivra ha-olam, “for my sake the world was created.” On the other he wrote a phrase from our father Avraham in the Torah: V’anokhi afar v’efer,” “I am but dust and ashes.” He would take out and read each slip of paper as necessary for the moment.

So perhaps that is what the small mem teaches us about the altar. On the one hand, we are small and humble in the face of the fire of the altar, and even more so the fire of G-d’s presence. On the other hand – it is our worship that lights the flame and allows us to connect to the infinite. It is up to us, according to Parshat Tzav, to keep the fire of the altar going.